At triglyceride levels ≥500 mg/dL,

accumulation of non-HDL-containing atherogenic lipoproteins, such as VLDL and cholesterol-rich remnant particles, increases the risk of ASCVD.1,4

To help better manage patients with sHTG, sign up and join a community of healthcare professionals receiving the latest resources and updates about severe hypertriglyceridemia (sHTG).

Intended for US healthcare professionals only.

Required fields.

Associated risks of severe hypertriglyceridemia (sHTG)

In sHTG, triglyceride levels and lipoprotein composition are closely linked to the risk of acute pancreatitis (AP) and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). Understanding how lipoproteins contribute to these risks can help you get a better picture of your patients' risk profile.1-3

The role of lipoproteins

Explore the relationship between lipoproteins and triglyceride levels to better understand the risks of severe hypertriglyceridemia (sHTG)

Acute pancreatitis risk

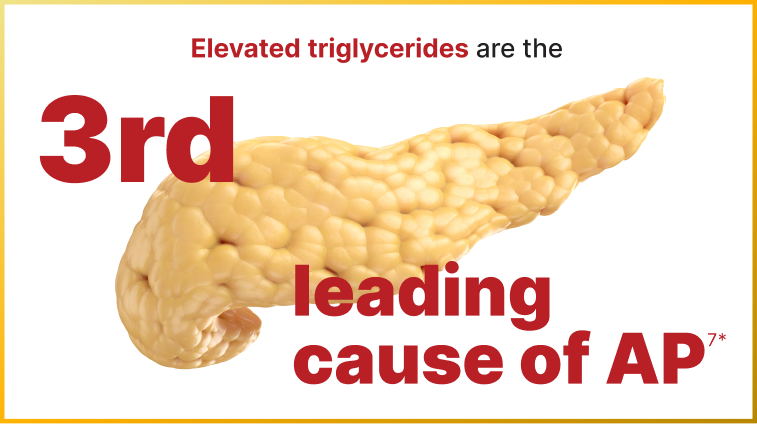

Severe hypertriglyceridemia (sHTG) increases the risk of potentially life-threatening acute pancreatitis (AP)1,7

the buildup of chylomicrons increases the risk of AP. As triglyceride levels continue to rise, the risk of AP increases.1,8,9

Based on Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline, elevated triglycerides (defined as serum triglyceride levels ≥150 mg/dL) were considered the third leading cause of AP following gallstones and alcohol.7

apoB-48=apolipoprotein B-48.

irreversible organ damage, including pancreatic necrosis

beta-cell dysfunction leading to pancreatogenic diabetes (type 3c)

death

Mortality rate as high as

Prolonged hospitalization of around

Healthcare costs averaging

~$100Kincluding hospital costs and the 12 months following an AP event10

Once a patient with sHTG has had an episode of AP, their risk for a second can be as high as

24%

11*After 2 or more episodes, the risk for another can increase to nearly

49%

11**In patients with triglyceride levels >1000 mg/dL.11

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk

Severe hypertriglyceridemia (sHTG) substantially increases a person’s risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD)1,12

At triglyceride levels ≥500 mg/dL,

accumulation of non-HDL-containing atherogenic lipoproteins, such as VLDL and cholesterol-rich remnant particles, increases the risk of ASCVD.1,4

Patients with sHTG are

as likely to have ASCVD events compared with patients with normal triglyceride levels12*

*Normal triglyceride levels were defined as <150 mg/dL.12

apoB-100=apolipoprotein B-100; HDL=high-density lipoprotein; VLDL=very low-density lipoprotein.

sHTG is independently associated with coronary heart disease (CHD)13

In a real-world study, the rate of CHD events was significantly higher in patients with sHTG compared with those who had normal triglyceride levels at baseline.13*

Rate of CHD events in patients with sHTG at baseline:

16.2%

Rate of CHD events in patients with normal triglyceride levels at baseline:

9.5%

The rate of new CHD events remained statistically significant at follow-up 11.3 years later.

*95% CI, 1.32-2.58; P<0.001.

Adults with primary isolated hypertriglyceridemia and at least 1 triglyceride level ≥500 mg/dL (n=517) between 1998 and 2015 in Olmsted County, Minnesota, were identified and matched with 766 controls with triglyceride levels <150 mg/dL. CHD was defined as myocardial infarction, surgical or percutaneous coronary revascularization, cardiac angina, high-grade stenosis on coronary angiography, or an abnormal stress test.13

Other risks

The full mental and physical impact of severe hypertriglyceridemia (sHTG) on patients is likely underestimated14

Symptoms reported by patients with sHTG in 2 studies aligned with Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) scores below population norm.14,15*†‡

Stress

Anxiety

Worry

Depression

Brain fog

Difficulty remembering things

Difficulty paying attention

Difficulty verbalizing thoughts

Gastrointestinal distress

Abdominal pain

Fatigue

Shoulder and back pain

A 6-month prospective observational study of US-based adults with sHTG to evaluate disease burden and treatment patterns based on app-based home-reported outcomes. Monthly in-app surveys were used to collect data on overall health and health-related quality of life, including PROMIS Cognitive Function.14

A qualitative interview study of adults with sHTG, very severe HTG, and/or familial chylomicronemia syndrome to explore the patient experience of hypertriglyceridemia-related AP. Participants experienced at least 1 episode of AP in the past 2 years requiring an overnight hospitalization. Participants completed a background questionnaire, the EQ-5D-5L (a generic health-related quality of life questionnaire), and select items from a PROMIS profile prior to interview.15

PROMIS is a system of standardized, patient-reported measures for assessing physical, mental, and social health in adults and children, used to measure health symptoms and health-related quality of life domains.16

AP=acute pancreatitis; HTG=hypertriglyceridemia.

References

Virani SS, Morris PB, Agarwala A, et al. 2021 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on the management of ASCVD risk reduction in patients with persistent hypertriglyceridemia: a report of the American College of Cardiology solution set oversight committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(9):960-993.

Yuan G, Al-Shali KZ, Hegele RA. Hypertriglyceridemia: its etiology, effects and treatment. CMAJ. 2007;176(8):1113-1120.

Rashid N, Sharma PP, Scott RD, Lin KJ, Toth PP. Severe hypertriglyceridemia and factors associated with acute pancreatitis in an integrated health care system. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10(4):880-890.

Ginsberg HN, Packard CJ, Chapman MJ, et al. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and their remnants: metabolic insights, role in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and emerging therapeutic strategies—a consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(47):4791-4806.

Kounatidis D, Vallianou NG, Poulaki A, et al. ApoB100 and atherosclerosis: what's new in the 21st century? Metabolites. 2024;14(2):123.

Goldberg RB, Chait A. A comprehensive update on the chylomicronemia syndrome. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:593931.

Nawaz H, Koutroumpakis E, Easler J, et al. Elevated serum triglycerides are independently associated with persistent organ failure in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(10):1497-1503.

Laufs U, Parhofer KG, Ginsberg HN, Hegele RA. Clinical review on triglycerides. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(1):99-109c.

Shemesh E, Zafrir B. Hypertriglyceridemia-related pancreatitis in patients with type 2 diabetes: links and risks. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2019;12:2041-2052.

Kessler AS, Kutrieb E, Soffer D, et al. Healthcare costs among acute pancreatitis patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia. J Clin Lipidol. 2025;19(3)(suppl):e118-e119. Scientific poster abstracts selected for the National Lipid Association 2025 Scientific Sessions; May-June, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2025.04.169

Sanchez RJ, Ge W, Wei W, Ponda MP, Rosenson RS. The association of triglyceride levels with the incidence of initial and recurrent acute pancreatitis. Lipids Health Dis. 2021;20(1):72.

Arca M, Veronesi C, D’Erasmo L, et al. Association of hypertriglyceridemia with all-cause mortality and atherosclerotic cardiovascular events in a low-risk Italian population: the TG-REAL retrospective cohort analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(19):e015801.

Saadatagah S, Pasha AK, Alhalabi L, et al. Coronary heart disease risk associated with primary isolated hypertriglyceridemia; a population-based study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(11):e019343.

Kessler AS, Zhang C, McStocker S, et al. Study-start characteristics of individuals with severe hypertriglyceridemia (sHTG) in an app-based home-reported outcomes study evaluating disease burden and treatment patterns. Abstract accepted for presentation at: PancreasFest; July 24-25, 2025; Pittsburgh, PA.

Kessler AS, Aggio D, Howard EM, et al. A qualitative study to explore the patient experience of hypertriglyceridemia-related acute pancreatitis. J Clin Lipidol. 2025;19(4):931-941.

What is PROMIS? PROMIS Health Organization. 2025. Accessed December 3, 2025. https://www.promishealth.org/57461-2/